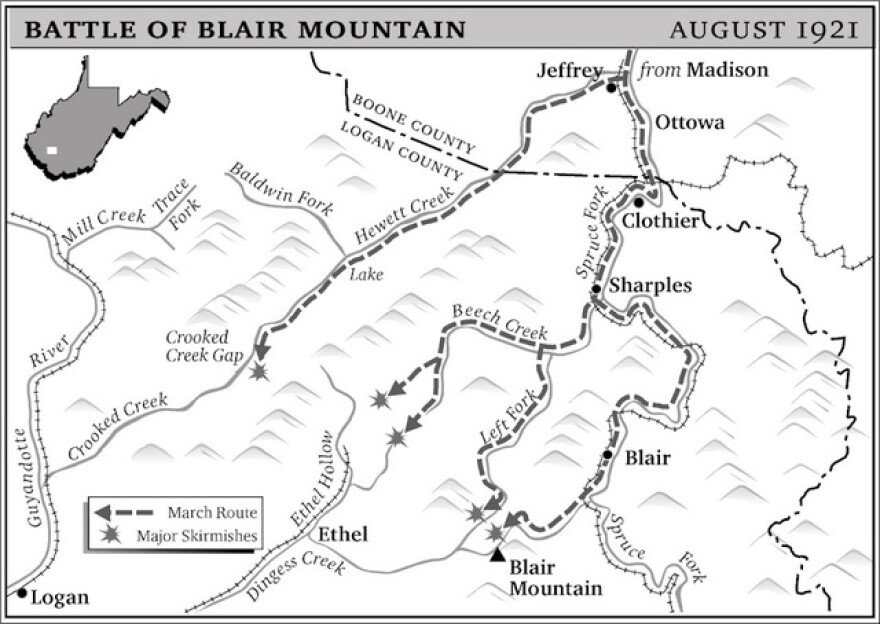

Map showing the Red Neck Army’s troop movements including major skirmishes and the three-flank tactic. (Heidi Perov, WV Humanities Council)

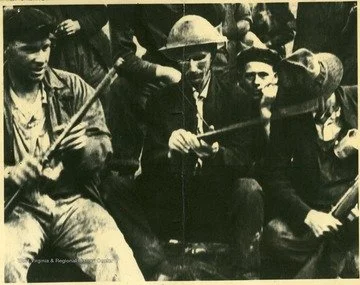

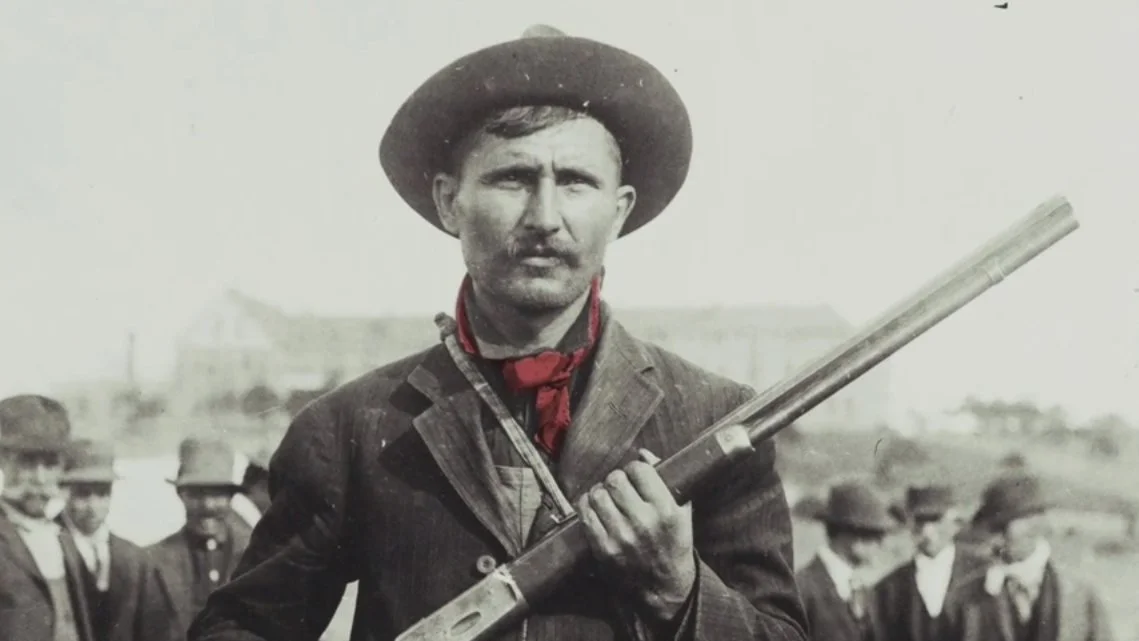

Leaving Marmet on August 25, the first wave of marchers had a singular focus: marching to Mingo County, freeing the illegally held miners, and bringing a union into southern West Virginia. Along the way, their numbers swelled to more than 10,000, as more and more men steamed out of the hollows and off the mountainside ready for a fight. Many men wore their WWI uniforms and carried their military firearms, others donned their red bandanas and brought whatever weapons they owned. At night, the mountainsides were afire with the army’s campfires.

As they followed the rocky creek beds and narrow paths snakingover and around the mountains, they created regiments and devised military tactics. Forming three flanks, the men moved toward Logan County where they knew they would face forces led by militantly anti-union Sherriff Don Chafin. Often referred to as the King of Logan County, Chafin vowed, “No armed mob of union men will cross the Logan County Line.” For their part, the miners often sang, “We’ll hang Don Chafin from a sour apple tree” to the tune of “John Brown’s Body.”

While the miners busied themselves building field hospitals, kitchens, rest stations, and ammo depots, much was going on behind the scenes in Charleston. Governor Morgan called out the National Guard and President Harding sent WWI General Bandholtz to West Virginia to put the rebellion down. Bandholtz warned union leaders Frank Keeney and Fred Mooney that any violence would prove disastrous for the miners and their union. Realizing that the Red Neck Army would take many casualties in such a confrontation, when Bandholtz proposed a ceasefire, they agreed. Together, they convinced the miners to stop the march and return to their homes. But as the angry miners boarded trains to return home, things took a turn for the worse.

After the ceasefire was announced, Sheriff Chafin, for reasons that remain unclear, sent 300 men into Sharples. A gun battleerupted and both miners and deputies were killed. When word of the breached ceasefire got back to the miners, Mooney and Keeney lost influence over the marchers and the assault began anew. The army headed toward Logan County, more angry and more determined than ever.

Miners preparing for a fight. (West Virginia and Regional HIstory Center, West Virginia University)

The town of Logan was protected by a natural barrier, Blair Mountain, located south of Sharples. Led by Bill Blizzard, seen by many as the field leader, the miners knew they could only reach Mingo—and their goals—if they crossed Blair Mountain and faced Chafin's forces. The anti-union forces took positions atop Blair Mountain. The miners assembled in Blair, near the mountain’s base. And the stage was set for all-out warfare.

The battle raged full throttle for four days. The anti-union defenders had a strategic advantage having dug trenches and set up machine gun nests along the ridge line. The miner’s advantage lay in their determination and sense of a righteous cause. The fighting was furious. On the third day of combat, anti-union forces called in civilian planes to drop bombs on the miners’ front lines.

Had the battle been allowed to play out, it is hard to imagine what might have been. But it did not play out, and we know only what was.

Member of the Red Neck Army (Public Domain)

On September 1, President Harding sent federal troops from Fort Thomas, Kentucky. Two days later, the first federal troops arrived at Jeffrey, Sharples, Blair, Clothier, and Logan. Considering themselves patriots, the miners were unwilling to fire on United States soldiers. As a result, the arrival of federal troops brought a quick end to the fighting.

Although some miners on the front lines continued fighting until September 4, most miners laid their weapons down on September 3 and boarded trains to return home. However, miners who were perceived by the military and mine owners to be the rebellion’s leaders were held to face a special grand jury. In the end, 1, 217 indictments were handed down charging 325 miners with murder and 24 with treason against the state.

Miners awaiting trial in Charles Town (West Virginia and Regional History Center)

In May 1922, the so-called Treason Trials were conducted in Charles Town, in the same courthouse where John Brown had been tried for treason 73 years earlier. The prosecutions were funded by mine owners and the defense by the United Mine Workers. Although few miners were found guilty, defending those charged bankrupted the United Mine Workers and their membership declined rapidly, greatly weakening their power for the next twelve years.

Although the miners didn’t achieve their goals, their actions did bring attention to the injustices in West Virginia’s mining industry. The power of their resistance stands today as perhaps the most important labor action in American history.

RSVP to the Community Monument Planning Meeting Here