But this was just the finale of a drama begun a decade earlier. In 1912, on Paint Creek and Cabin Creek, miners and their families went on strike, formed tent colonies, and withstood harsh winter conditions and deadly attacks to protest deplorable conditions in the mines and company-controlled towns. After a year, they had won important concessions and organized into locals of the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA). Their movement continued to spread, but Logan, Mingo, and McDowell counties remained nonunion territory.

Shell casings from the Battle of Blair Mountain, unearthed by Kenneth King nearly 70-90 years after the fact.

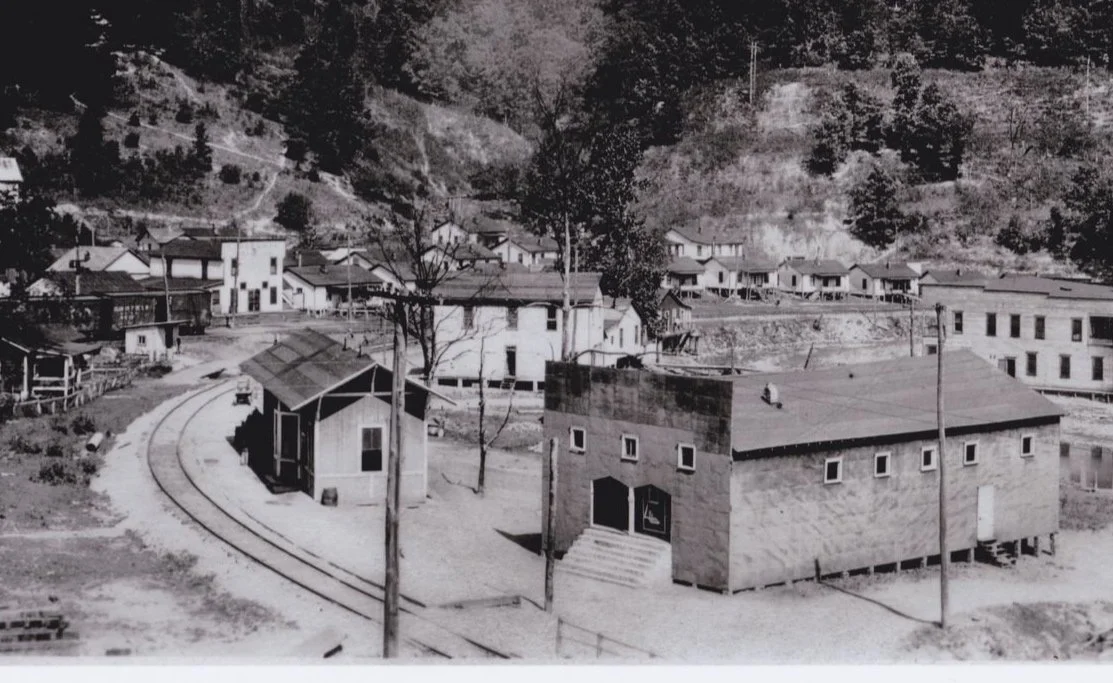

Town of Matewan, WV

Then in May 1920, miners in Mingo County went on strike. Sid Hatfield, the chief of police of Matewan, became the miners’ hero when he temporarily halted the mine guards’ evictions. When the guards later tried to arrest Hatfield, the battle that followed left seven mine guards, two miners, and the mayor of Matewan dead.

Governor Ephraim Morgan declared county-wide martial law in Mingo in response to the shootout. The state's crackdown was severe and only applied to unionizing miners, not the coal company agents who had also incited violence: Union activists were jailed without trial, and miners' families were assaulted in their makeshift camps.

Then, on August 1, 1921, Hatfield and his deputy Ed Chambers were murdered by mine guards on the McDowell County courthouse steps while unarmed and accompanied by their wives. The murders epitomized the ordinary worker's helplessness to resist the brutality of the mine guard system. Many miners now believed they were in a battle to reclaim their basic rights as American citizens, but their pleas to Governor Morgan went unanswered. They arrived in Marmet by the hundreds, rifles in hand, and formed an encampment on Lens Creek. White and Black, native-born and immigrant, they donned red bandanas as a symbol of their solidarity, becoming known as the “Redneck Army.” The general of this army was Bill Blizzard, a 28-year-old miner from Cabin Creek who had joined the UMWA during the 1912-1913 strike at the urging of his mother and union activist Sarah Blizzard.

The Redneck Army planned to free their compatriots from jail, help win the Mingo strike, and unionize the southern counties. First, they would have to go through Logan County where Sheriff Don Chafin, whose salary was paid by coal operators, had assembled an army of three thousand deputies and mine guards. Chafin’s “Logan Defenders,” armed with machine guns, took defensive positions along Blair Mountain’s 15-mile ridgeline.

Chief of Police Sid Hatfield (right) and Ed Chambers (left) were murdered on the steps of McDowell county Courthouse in 1921.

-West Virginia State Archives

A photo of leading members of the United Mine Workers of America. Bill Blizzard is on the far left, followed by Fred Mooney, William Petry, and Frank Keeney.

-West Virginia & Regional History Center

Columns of miners began their assault on August 31.

Led by World War I veterans, they were disciplined, remaining behind cover and attempting to flank heavily guarded positions. For four days, the chatter of automatic weapons and the crack of rifles echoed around Blair Mountain.

Hub Bane's Red Bandana from the Battle of Blair Mountain, on loan at the West Virginia Mine Wars Museum.

Heidi Perov

-WV Humanities Council

Miners gather near Blair, WV.

Nurses accompany Redneck Miners Army

The Redneck Army depended on numerous allies. Volunteer nurses with “UMW” on their hats set up a makeshift hospital. Supporters along the march route donated supplies and arms. Volunteers like Isabella Riggs in Blair prepared hundreds of meals each day.

The bitter fighting made national headlines. President Warren Harding dispatched four regiments of the US Army that arrived on September 3.

The miners had no interest in fighting “Uncle Sam.” Blizzard negotiated a ceasefire the next day, and the Redneck Army withdrew from the battlefield, some surrendering their weapons to the army.

Hundreds of miners were indicted on charges including murder and treason. At the Treason Trials the following year in Charles Town, a jury acquitted Blizzard, leading prosecutors to drop most of the charges against others. Chafin and the coal operators were never charged with any wrongdoing. In fact, coal company lawyers led the prosecution against the miners, for which the state of West Virginia was later billed.

The underlying conditions that led to the uprising—company towns, company stores, poor wages, dangerous conditions, and brutal mine guards—remained for another decade until changes in federal labor laws gave the miners another chance to unionize.

Why Did The Miners Fight?

Coal miners and their families everywhere have historically faced difficult conditions, but West Virginia at this time was especially contentious. Mine owners had near total control: Miners were paid in scrip, redeemable only at the company store, and the company towns where they lived were patrolled by private police or "mine guards." To prevent workers from the unionizing, companies recruited immigrants from Europe, African Americans from the South, and Appalachians from nearby farms, assuming their differences would keep them divided. Supervisors blacklisted workers suspected of having union sympathies, preventing them from working at other mines. Mine guards evicted them and their families by force, casting their belongings into the street. Objections to the mine guard system were the miners' principal grievance during the West Virginia Mine Wars.

Detail, Battle of Blair Mountain:

Celebrate People’s History poster by Chris Stain.